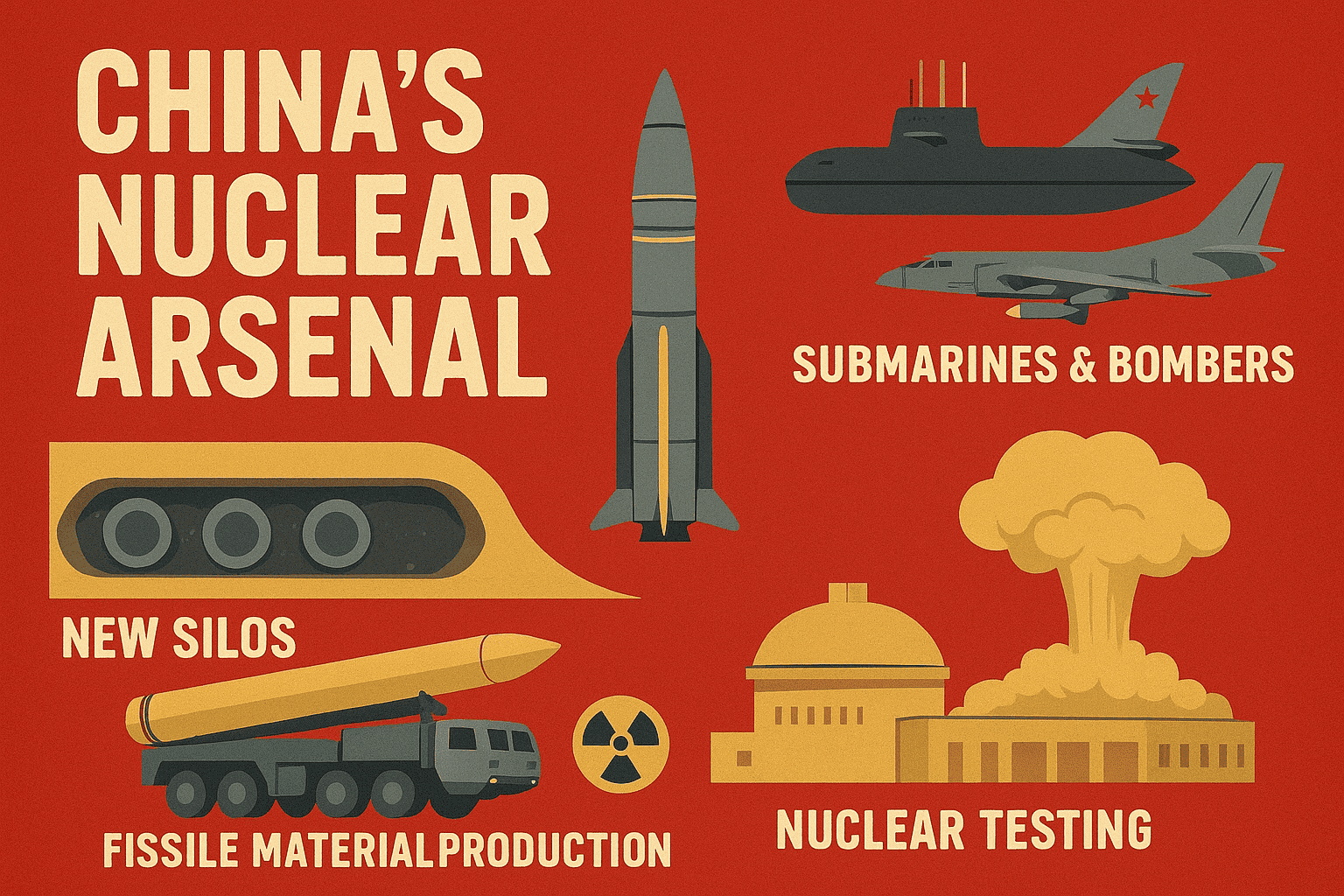

China’s nuclear arsenal has undergone significant modernization and expansion in recent years. The country is estimated to possess approximately 600 nuclear warheads, with more in production, to arm futuristic land-based ballistic missiles, sea-based ballistic missiles, and bombers. The country is constructing 320 new silos for its intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), including the liquid-fuelled DF-5B equipped with multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicle (MIRV) technology. Additionally, China is refitting its Type 094 ballistic missile submarines with the longer-range JL-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile. The country’s fissile material production is also increasing, with the completion of its first civilian “demonstration” reprocessing plant of the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) at Gansu Nuclear Technology Industrial Park, giving ability to produce more nuclear warheads in the future. China now has the fastest-growing nuclear arsenal among the nine nuclear-armed states. It is the only Party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) that is significantly increasing its nuclear arsenal.

Image Credit: Reuters

China’s nuclear doctrine, and “no-first-use” policy have remained relatively consistent since its first nuclear test in 1964. China’s nuclear expansion has also triggered speculations about its nuclear intentions, with some US officials suggesting that China seeks to match or surpass the US nuclear arsenal. The Pentagon has projected that China’s nuclear arsenal could surpass 1,000 warheads by 2030, and field a stockpile of about 1,500 nuclear warheads by 2035. China calls these “sensationalized” or “exaggerated” claims. The country has not conducted nuclear tests since 1996, but recent construction at the Lop Nur test site has raised concerns about its intentions. The US has expressed concerns about the country’s adherence to the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). But Chinese warheads are not operationally deployed on missiles or placed at bomber bases like the US and Russia. Nearly all Chinese warheads are thought to be stored separate from the launchers. China’s growing nuclear program has significant implications for global security and the balance of power.

Fissile Materials Production

China’s nuclear stockpile growth depends directly upon its inventories of plutonium, highly enriched uranium (HEU), and tritium. The International Panel on Fissile Materials assessed in 2023 that China had a stockpile of approximately 14 tonnes of HEU and approximately 2.9 tonnes of separated plutonium. Such inventories were sufficient to increase to approximately 1,000 warheads by 2030. China stopped producing weapon-grade plutonium a few decades back. But it is believed that China sources significant stocks of plutonium from its civilian reactors. Russia’s state-controlled nuclear energy company, Rosatom, delivered initial fuel for China’s CFR-600, a sodium-cooled pool-type fast-neutron nuclear reactor under construction in Xiapu County, Fujian province. The second reactor is scheduled to come online by 2026. Construction of a third plant is expected to be completed in the early 2030s. If the fast-breeder reactors operate as planned, they could potentially produce large amounts of plutonium including weapon-grade.

Image Credit: Britannica Encyclopedia

Meanwhile, the Pentagon assesses, China is expanding and diversifying its capability to produce tritium at its two large new centrifuge enrichment plants at Emeishan and Lanzhou. China’s production and reprocessing of fissile materials is thus largely consistent with its nuclear power and weapons plans. Currently very secretive, China may become more transparent about its nuclear forces if it more readily participates in arms control consultations.

Nuclear Testing

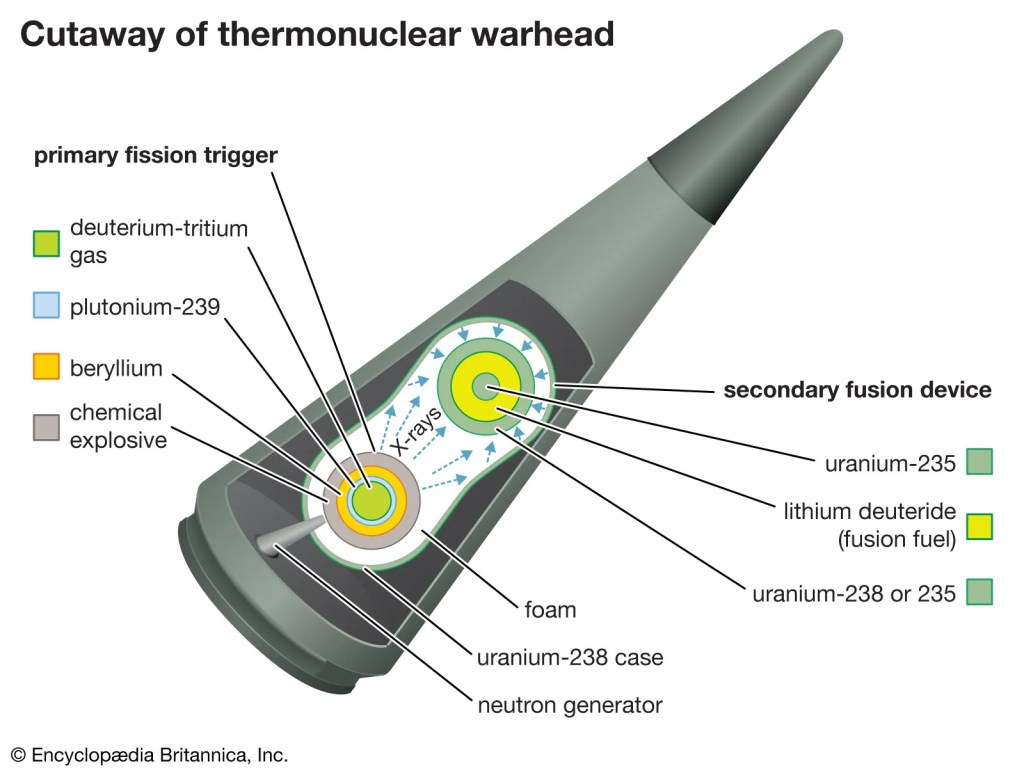

The Chinese nuclear stockpile also depends on the size and design of its warheads. China’s nuclear testing program of the 1990s allowed development of the warheads currently arming the DF-31-class ICBMs. The same warhead design may also have been used to equip the liquid-fuelled DF-5B ICBM with MIRV technology. The large DF-41 and the JL-3 missiles could also use the same smaller warhead. China reportedly also seeks a “lower-yield” nuclear warhead for the DF-26. Developing any significantly different warhead designs would perhaps require additional nuclear test explosions. To avoid physical tests, China could use advanced computer simulations, and/or very low-yield underground explosive tests. Open-source satellite imagery shows significant construction at the Lop Nur site with nearly a dozen concrete buildings and underground facilities. Should China conduct even a low-yield nuclear test it would violate the CTBT it has signed though not ratified.

DF: 41

Image Credit: Observer Research Foundation

Land-based Ballistic Missile Launchers and Brigades

The PLA Rocket Force (PLARF) currently operates approximately 712 launchers for land-based missiles that can deliver nuclear warheads. Of those launchers, 462 can be loaded with ICBMs that can target around the globe. Many of China’s ballistic missile launchers are for short, medium, and intermediate-range missiles intended for regional, non-nuclear strike missions. China is estimated to have roughly 100 nuclear warheads assigned to regional missiles. Many of these could be for targets in India and Japan. The PLARF controls nine dedicated bases, including six for missile operations distributed across China. Each missile operating base controls six to eight missile brigades, totalling around 45 brigades. The number of launchers and missiles assigned to each brigade depends on the type of missile. Nearly 30 of those brigades are meant to operate ballistic missile launchers with nuclear capability.

The 320 new silos for solid-fuel missiles and the construction of 30 new silos for liquid-fuel missiles in three mountainous areas of central-eastern China is a significant development. The silos are positioned roughly three kilometres apart. The silo fields are located deeper inside China than any other known ICBM base, and beyond the reach of the United States’ conventional and nuclear cruise missiles. It is estimated that around 10 silos in each missile field may have been loaded.

Among the new silo fields, the Yumen field, in Gansu province in the west, covers an area of approximately 1,110 square kilometres, and has 120 individual silos. The Hami field, located in Eastern Xinjiang, spans an area of approximately 1,028 square kilometres, and has 110 missile silos. The Yulin field, located near Hanggin Banner, is smaller, measuring 832 square kilometres and has 90 missile silos. The 350 new Chinese silos under construction exceed the number of silo-based ICBMs operated by Russia and constitute about three-quarters the size of the entire US ICBM force. Each field has very secure storage and significant air defences. Analysis of satellite imagery shows that the three fields may still be some years away from full operational capability.

China’s ICBM Force Developments

China has around 400 ICBMs in its inventory. That indicates that China may still be producing missiles for the new launchers. The DF-31 solid-fuel road-mobile ICBM has a range of 7,200 kilometres. Range and manoeuvrability were extended in subsequent variants. The silos may be loaded with DF-31-class ICBMs or a mix of DF-31As (11,200 kilometres) and DF-41s. The new DF-31AG eight-axle launcher is thought to carry the same missile as the DF-31A launcher but has improved off-road capabilities. The DF-41 could carry up to three MIRVs. Presently, each of China’s ICBM missile brigades is responsible for six to 12 launchers. How will the silo fields be allocated? Will there be some new PLARF Bases, each with several brigades?

The DF-5A and the MIRVed DF-5B are already deployed. The DF-5B can carry up to five MIRVs. A third variant with a “multi-megaton yield” warhead, the DF-5C, is currently being fielded. In February 2023 China conducted a developmental flight test of a multirole “hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV)” for the DF-27. An operational FOB/HGV system would pose challenges for missile tracking and missile defence systems, as it could theoretically orbit around the Earth and release its manoeuvrable payload unexpectedly with little detection time.

Medium and Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missiles

The dual-capable DF-26 MRBM and IRBM launchers have increased from 18 to 250, with 500 missiles in 2024. With approximately 4,000-kilometre range, the DF-26 can target Japan, South Korea, important US bases in Guam, as well as large parts of Russia and all of India. It seems unlikely that all DF-26s are assigned a nuclear mission. The DF-26’s anti-ship version is non-nuclear. Among the other two DF-26 versions only a few may be used for a nuclear mission. The DF-26’s capability of rapidly swapping warheads, even after the missile has been loaded onto its launch vehicle, creates command and control risks and the potential for misunderstandings in a crisis. China is one of several countries (including India, Pakistan) that mix nuclear and conventional capabilities on MRBMs and IRBMs. Though the command and control are clearly separated in the case of India. China was making an “investment in lower-yield, precision systems with theatre ranges.” The DF-17 is a Chinese road-mobile MRBM designed to carry the DF-ZF HGV. It’s a key part of China’s hypersonic weapon arsenal and is considered a significant technological advancement.

Submarines and Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBM)

China currently fields a submarine force of six second-generation Jin-class (Type 094) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), which are based at the Yalong naval base on Hainan Island. The new Type-94A variants are meant to be less noisy, and equipped with 12 launch tubes each. The JL-2 SLBM has a range of 7,200 kilometres, sufficient to target Alaska, Guam, Hawaii, Russia, and India from waters near China. The longer-range JL-3 SLBMs have a range of 10,000 kilometres, and can target continental United States if it sails deep into the Pacific Ocean. Unlike the JL-2, the JL-3 reportedly can deliver “multiple” warheads per missile. The new Type 096 was scheduled to begin construction in the early 2020s, but there have been delays. These will be larger, heavier, and quieter, and would be a significant technological leap for China. Some speculate that the Type 096 will carry 24 missiles. The service life of these two types is expected to be 30 to 40 years and will be in operations together. China may settle for a fleet of eight to 10 SSBNs.

China had reportedly begun “near-continuous at-sea deterrence patrols with its six SSBNs” in 2021, implying that the SSBN fleet is not on patrol all the time but that at least one boat is deployed intermittently. The term “deterrence patrol” implies that the submarine at sea has nuclear weapons on-board. Giving custody of nuclear warheads to deployed submarines during peacetime would constitute a significant departure for China’s CMC, which has traditionally been reluctant to hand out nuclear warheads to the armed services. China is presumably improving its command-and-control system to ensure reliable communication with the SSBNs when needed and prevent the crew from launching nuclear weapons without authorization. The Western allies are trying to constantly track Chinese submarines.

Bombers

China developed several types of aircraft-deliverable nuclear bombs and test-dropped at least 12 that detonated between 1965 and 1979. Later, however, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) nuclear mission became dormant as the rocket force improved and older intermediate-range bombers were not considered useful for a nuclear conflict. But later in 2017-18 China reportedly reassigned ballistic missile missions to the H-6N “Badger” bomber. The H-6N can carry six air-launched ballistic missiles (ALBM), an air-launched version of the YJ-21 sea-launched anti-ship ballistic missile. Aircraft also got an in-flight refuelling probe, increasing range. Initially expected to be for only conventional strike, but in late 2024, there were indications that the CH-AS-X-13 nuclear ALBM had been deployed. Thus, China re-established the viable nuclear “triad.” Currently, only one PLAAF unit is reportedly having a nuclear mission. Large tunnel entrances have been built into a nearby mountain wide enough to accommodate the H-6N bomber at this airbase in Henan province. Around 20 H-6N bombers have the nuclear role. China is developing a stealth bomber, H-20, with a longer range (20,000 km), aerial refuelling, and improved capabilities. It is suspected that some Chinese cruise missiles might have nuclear capability and may equip the H-20.

Are Chinese Nuclear Numbers Really Catching Up With USA?

While the West continues to speculate on Chinese warhead numbers, the Chinese government keeps it ambiguous by neither denying nor accepting the expansion. US officials propound that China has moved away from its longstanding “minimum deterrence” posture, and that it seeks to match, or in some areas surpass, quantitative and qualitative nuclear parity with the United States. China wants to be a nuclear “peer” or “near-peer” in the future. But that seems far-fetched. Even the 1,500 warheads by 2035 will still be less than half of the current US nuclear stockpile.

Chinese Nuclear Doctrine and Policy

China remains committed to “no first use” of nuclear weapons at any time and under any circumstances, and not using or threatening to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states unconditionally. China’s nuclear strategy is of self-defence, by deterring other countries from using or threatening to use nuclear weapons against it. It thus had plans to keep its nuclear capabilities at the minimum level required for national security, and “strategic counterbalance.” How large the “minimum” capability is, is not defined. The extraordinary current expansion of China’s nuclear arsenal includes building the nuclear counterattack capability and conventional strike capability. China is practicing “nuclear attack survival exercises” to ensure that troops could still launch nuclear counterattacks if China were to be attacked. It is also improving early-warning systems and the stealth capabilities of its nuclear forces. China’s nuclear strategy may now include consideration of a nuclear strike in response to a non-nuclear attack threatening the viability of China’s nuclear forces or their Command and Control. China’s stance is that it will not attack unless attacked, but it will surely counterattack if attacked.

Nuclear Forces Readiness

The PLA keeps most of its warheads at its regional storage facilities, or its central hardened storage facility in the Qinling mountain range. A part of its units are on a heightened state of readiness. PLARF brigades conduct “combat readiness duty” drills. But corruption within the PLA had led to an erosion of confidence in its overall capabilities. The poorly constructed silos in connivance with corrupt officials have since been repaired. Lack of trust in top defence officials might force President Xi Jinping not to order to arm missiles with warheads in peacetime. Any nuclear attack is only likely to follow a period of increased tension and possibly conventional warfare, giving enough time to mate warheads to the missiles. With launchers secured and dispersed, including in tunnels, it is impossible that at least some of its missiles will not remain intact for a retaliatory strike. The Central Military Commission (CMC) will decide the nuclear alert status.

The many new silos for quick-launch solid fuel missiles (DF-5s), and road-mobile ICBMs, and development of a space-based early warning system indicate China’s intent to move to a launch-on-warning (LOW) posture, or “early warning counterstrike,” allowing China to launch its missiles before they would be destroyed. China is planning to have at least three early-warning satellites in orbit. PLARF is already practicing “launch-on-warning” scenarios. Interestingly, both the United States and Russia operate large numbers of solid-fuel silo-based missiles and early-warning systems to launch their missiles before they are destroyed.

To Summarise

China is already fielding an indigenous HQ-19 anti-ballistic missile system and developing an “ultra-long-range” missile defence system as well as hit-to-kill mid-course technology that could engage IRBMs and possibly ICBMs. China already maintains several ground-based large phased-array radars that contribute to its nascent early-warning capabilities. The modernization of the nuclear forces could gradually offer, in the future, the Chinese leadership more efficient ways of deploying, responding, and coercing with nuclear or dual-capable forces. Could China leverage nuclear weapons in its “counter-intervention” strategy that aims to limit the US presence in the East and South China Seas and achieve reunification with Taiwan? Yet, it is clear that China’s no-first-use policy probably has a high threshold. Beijing could consider nuclear first use if a conventional military defeat in Taiwan gravely threatened the Chinese Communist Party regime’s survival. China’s nuclear readiness and overall nuclear strike capability will force improvements in the Russian, Indian, and US nuclear arsenals. India currently has nearly 180 nuclear warheads. This figure, some analysts believe, should go up to 400. India needs to have a robust Command and Control system and second-strike capability. Most importantly, India must have a credible conventional capability, as nuclear wars are unlikely.

Header Picture Credit: Author

Twitter: @AirPowerAsia