While aces are generally thought of exclusively as fighter pilots, but such status has been also accorded to gunners on bombers or reconnaissance aircraft, and to observers in two-seater fighters such as the early Bristol F-2b, and Navigators/weapons officers in aircraft like the F-4 Phantom. Because pilots often teamed with different air crew members, an observer or gunner might be an ace while his pilot is not, or vice versa. Observer aces constitute a sizable minority in many lists. Charles George Gass, who tallied 39 victories, was the highest scoring observer ace in World War I.

In World War II, United States Army Air Forces B-17 tail gunner S/Sgt. Michael Arooth (379th Bomb Group) was credited with 17 victories. The Royal Air Force’s leading bomber gunner, Wallace McIntosh, was credited with eight kills, including three on one mission. Flight Sergeant F. J. Barker scored 13 victories while flying as a gunner in a Boulton Paul Defiant turret fighter piloted by Flight Sergeant E.R. Thorne.

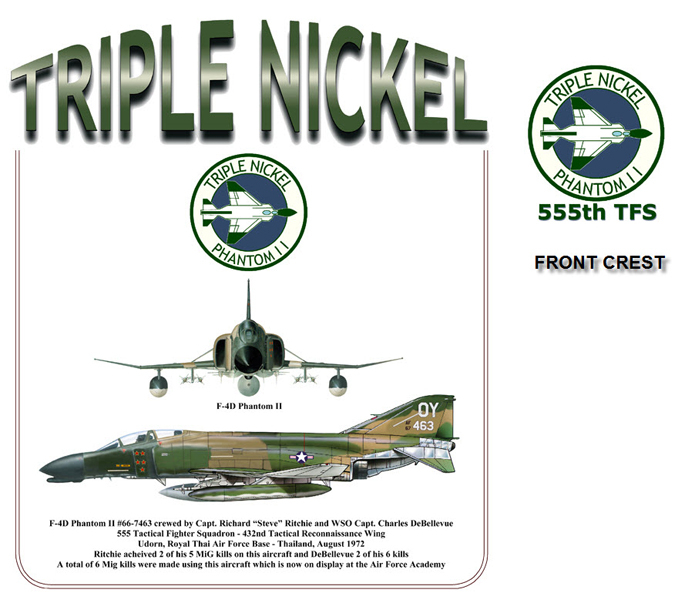

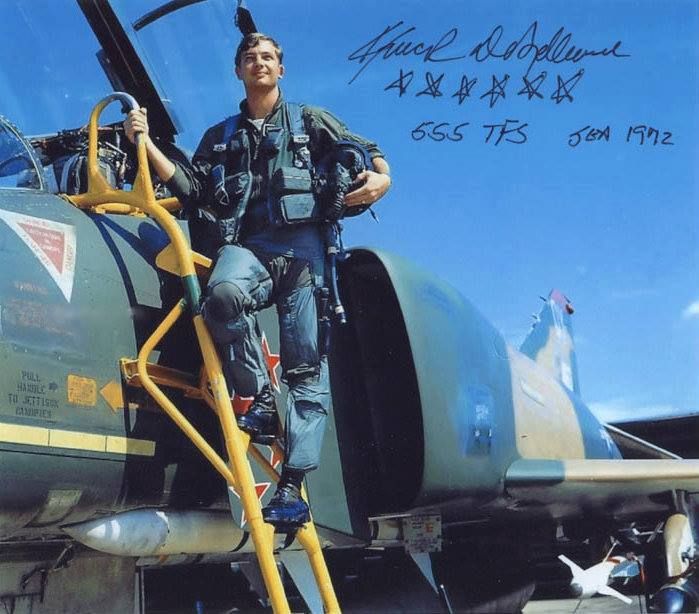

With the advent of more advanced technology, a third category of ace appeared. Charles B. DeBellevue became not only the first U.S. Air Force weapon systems officer (WSO) to become an ace but also the top American ace of the Vietnam War, with six victories. Close behind with five were fellow WSO Jeffrey Feinstein and Radar Intercept Officer William P. Driscoll. Colonel Charles Barbin DeBellevue is a retired officer of the United States Air Force (USAF). In 1972, DeBellevue became one of only five Americans to achieve flying ace status during the Vietnam war, and the first as an Air Force WSO, an integral part of two-man aircrews with the emergence of air-to-air missiles as the primary weapons during aerial combat. He was credited with a total of six MiG kills, the most earned by any U.S. aviator during the Vietnam War, and is a recipient of the Air Force Cross.

Joins USAF

DeBellevue was born in New Orleans on August 15, 1945, and grew up in Louisiana. After applying unsuccessfully to the USAF Academy, he attended and graduated from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (then named the University of Southwestern Louisiana), in 1968. Upon graduation, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant through the Air Force Reserve Officers Training Corps (AFROTC) program at the university. Accepted into Undergraduate Pilot Training (UPT), he failed to complete the course, but subsequently applied for and was accepted into Undergraduate Navigator Training (UNT) at Mather Air Base California in July 1969. He completed F-4 combat crew training, and was assigned to the 335th Tactical Fighter Squadron as a McDonnell Douglas F-4D weapon systems officer (WSO).

Vietnam War – First MiG Kill

In October 1971, DeBellevue was sent to the famed 555th “Triple Nickel” Tactical Fighter Squadron, of the 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing, at Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand. Flying in a F-4D as the WSO with pilot Capt Steve Ritchie on May 10, 1972, he and Ritchie scored the first of the four Mikoyan MiG 21 kills they would achieve together. Both DeBellevue and Ritchie, along with Capt Jeffrey Feinstein of the 13th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing, would become the only USAF “aces” during the Vietnam War. May 10, 1972 was the same day that Cunningham and Driscoll scored their third, fourth and fifth aerial victories, becoming the Navy’s only aces of the war.

An advantage that the “Triple Nickel Squadron” pilots and WSOs had over other U.S. aircrews was that eight of their F-4D Phantoms had the top-secret APX-80 electronic set installed, known by its code-name “Combat Tree”. Combat Tree could read the IFF signals of the transponders built into the MiGs so that North Vietnamese GCI radar could discriminate its aircraft from that of the Americans. Displayed on a scope in the WSO’s cockpit, Combat Tree gave the Phantoms the ability to identify and locate MiGs when they were still beyond visual range (BVR).

MiGCAP

MiGCAP was the term used primarily during the Vietnam War. A MiGCAP was directed specifically against MiG aircraft. MiGCAP during Operation Linebacker became highly organized and meant, an ingress MiGCAP of 2–3 flights (8–12 fighters) that preceded the first supporting forces such as chaff bombers or SAM suppressors and remained until they departed the hostile zone. A target area MiGCAP of at least 2 flights that immediately preceded the actual strikers; and an egress MiGCAP of 1 or 2 flights that arrived on station at the projected exit point ten minutes prior to the earliest egress time. All egress MiGCAP flights were fully fueled from tankers and relieved the target area CAP.

The First Major Day of Air Combat

Ritchie and DeBellevue’s assignment on May 10, 1972, the first major day of air combat in Operation Linebacker, was as element leader (Oyster 03) of one of two flights of the F-4D MiGCAP for the morning strike force. Oyster flight had three of its Phantoms equipped with Combat Tree IFF interrogators, and two days previously its flight lead, Major Robert Lodge, and his WSO Captain Roger Locher had scored their third MiG kill to lead all USAF crews then flying in Southeast Asia. At 0942, forewarned 19 minutes earlier by the EC-121 “Disco” over Laos and then by “Red Crown”, the US Navy radar picket ship USS Chicago, Oyster flight engaged an equal number of MiG-21s head-on, scattering them. Oyster flight shot down three and nearly got the fourth, but fell victim to a MiG tactic dubbed “Kuban tactics” after those of the Soviet World War II ace Pokryshkin, in which a GCI-controlled flight of MiG-19s trailed so that they could be steered behind the American fighters maneuvering to attack the MiG-21s. The F-4 flown by Lodge and Locher was shot down. Major Lodge was killed, Capt. Locher ejected and was rescued three weeks later. Almost simultaneously Ritchie and DeBellevue rolled into a firing position behind the remaining MiG-21 of the original four with a radar lock, launched two Sparrows and scored a kill with the second.

July 8, 1972, MiG Kills 2 and 3

USAF strike and chaff forces suffered a severe series of losses to MiGs between June 24 and July 5 (seven F-4s) without killing a MiG in return. As a counter-measure, 7th Air Force added a second Disco EC-121 to its airborne radar coverage, positioning it over the Gulf of Tonkin. On July 8, 1972, Ritchie and DeBellevue were leading Paula flight, in gun-equipped F-4Es instead of the Combat Tree F-4Ds they usually flew, on a MiGCAP to cover the exit of the strike force. While they were west of Phu Tho and south of Yen Bai, the EC-121 vectored them to intercept MiG-21s returning to base after damaging one of the US chaff escorts. The MiGs were still approximately 4 miles away and Ritchie turned the flight south to cross the Black River. As they closed, Disco gave them warning that the MiG return had “merged” with the Paula flight’s return on his screen. Ritchie reversed course, observed the first MiG at his 10 o’clock position and turned left to meet it head-on. When Ritchie passed the first MiG-21, he recalled the engagement of May 10 and waited to see if there was a trailing MiG. When he observed the second MiG, which he also passed head-on, he reversed hard left to engage. The MiG turned to its right to evade the attack, an unusual maneuver, and Ritchie used a vertical separation move to gain position on its rear quarter. DeBellevue obtained a solid bore-sight radar lock on it while at the MiG’s 5 o’clock, although fired from the edge of the flight envelope of AIM-7s. Both missiles struck home.

The first MiG had also turned back and was attacking the last F-4 in Ritchie’s flight from behind, an often fatal consequence to US aircraft employing the then-standard “fluid four” tactical formation. Ritchie made a hard turn across the curving intercept of the MiG, again coming out at its 5 o’clock, and the MiG, apparently perceiving the threat, broke hard right and dove away. Ritchie fired an AIM-7 from inside its minimum range and at the limit of its capability to turn. Expecting the Sparrow to miss, he was trying to switch to a gun attack in the relatively unfamiliar F-4E he was flying that day when the missile exploded the MiG, 1 minute and 29 seconds after the first kill.

Competition To Become USAF’s first Vietnam “ace”

A competition to become the Air Force’s first Vietnam “ace” developed between Ritchie and Captain Jeffrey S. Feinstein, a WSO in another one of the 432nd’s squadrons, the 13th TFS, who scored his 3rd and 4th kills on July 18 and July 29. Each had a claim denied by Seventh Air Force’s Enemy Aircraft Claims Evaluation Board, Ritchie and DeBellevue for a claim of a MiG-21 on June 13, and Feinstein for a claim June 9.

August 28, 1972, MiG Kill 4

Ritchie’s final victory (his 5th making him an “ace”) with DeBellevue (his 4th) came on August 28, 1972, while leading Buick flight, a MiGCAP for a strike north of Hanoi. During the preceding month, 7th Air Force had instituted daily centralized mission debriefings of leaders and planners from all fighter wings called “Linebacker Conferences”. Ritchie had just started his flight of Combat Tree Phantoms on its return to base (Ritchie and DeBellevue were flying F-4D AF Serial No. 64-7463, in which they had scored their first kill). Red Crown, now the USS Long Beach, alerted the strike force to “Blue Bandits” (MiG-21s) 30 miles southwest of Hanoi, along the route back to Thailand. Approaching the area of the reported contact at 15,000 feet, Ritchie recalled recent Linebacker Conference information that MiGs had returned to using high altitude tactics and suspected the MiGs were high. Buick and Vega flights, both of the MiGCAP, flew toward the reported location.

DeBellevue picked up the MiGs on the Phantom’s onboard radar and using Combat Tree, discovered that the MiGs were ten miles behind Olds flight, another flight of MiGCAP fighters returning to base. Ritchie called in the contact to warn Olds flight. Ritchie, concerned that MiGs might be at an altitude above them, made continuous requests for altitude readings to both Disco and Red Crown. He received location, heading, and speed data on the MiGs (now determined to be returning north at high speed to their base) but not altitude as Buick flight closed to within 15 miles of the MiGs. DeBellevue’s radar then painted the MiGs dead ahead at 25,000 feet, and Ritchie ordered the flight to light afterburners. DeBellevue warned Ritchie they were closing fast and were in range. About the same time Ritchie saw the MiGs himself headed in the opposite direction.

Attacking in a climbing curve behind the MiG-21’s with his AIM-7 guidance radar locked on, Ritchie was given continuous range updates by DeBellevue. With his Phantom barely making enough speed to overtake the targets, Ritchie launched two Sparrows from over four miles away. The firing parameters of the two shots were out of the missiles’ performance envelope, an attempt to influence the MiGs to turn and thus shorten the range. Both shots not only missed but failed to influence the opponents. Moments later, tracking one MiG visually by the contrail it was making, Ritchie fired his remaining two Sparrows, also at long range. The first missed, but the MiG made a hard turn and actually shortened the range, and was destroyed by the second. Short on fuel, Ritchie elected not to try to pursue the second MiG-21. That was Ritchie’s final victory (his 5th making him an “ace”)

September 9, 1972, “Ace Day”, MiG Kills 5 and 6

During Linebacker strikes on September 9, 1972, a flight of four F-4Ds on MiGCAP west of Hanoi shot down three MiGs. Following his fifth kill, Steve Ritchie had been removed from active combat. Two were MiG-19s downed by the new team of Capt John A. Madden, Jr. and his WSO Capt DeBellevue. For Madden, the victories constituted his first and second MiG kills, but for DeBellevue they were numbers five and six, moving him up as the leading MiG destroyer of the war and elevating him to “Ace” status. When DeBellevue acquired the MiGs on radar, the flight maneuvered to attack. Madden and DeBellevue made the first move. They got a visual on the MiG about 5 miles out on final approach with his gear and flaps down. Getting a lock on him, they fired missiles but they missed. They were coming in from the side-rear and slipped up next to that MiG no more than 500 feet apart. “He got a visual on us, snatched up his flaps and hit afterburner, accelerating out. It became obvious we weren’t going to get another shot at the MiG“, says DeBellevue.

DeBellevue Explains the Two Engagements

DeBellevue describes the next two engagements. “We acquired the MiG’s on radar and positioned as we picked them up visually. We used a slicing low-speed yo-yo to position behind the MiG-19’s and started turning hard with them. We fired one AIM-9L missile which detonated 25 feet from one of the MiG-19’s. We switched the attack to the other MiG-19 and one turn later we fired an AIM-9 at him. I observed the missile impact the tail of the MiG. The MiG continued normally for the next few seconds, then began a slow roll and spiraled downward, impacting the ground with a large fireball.“

Madden and DeBellevue returned to their base thinking they had destroyed only the second MiG-19. Only later did investigation reveal that they were the only aircrew to shoot at a MiG-19 which crashed and burned on the runway at Phuc Yen that day. That gave them two MiG-19 kills for the day and brought DeBellevue’s total to six MiG kills, the most earned during the war.

Flying Summary and Honour

During his combat tour, DeBellevue logged 550 combat hours while flying 220 combat missions, 96 of which were over North Vietnam. His skill as a weapon systems officer was recognized when he and the other two Air Force “Aces”, Ritchie and Feinstein, received the 1972 “Mackay Trophy”. The Mackay Trophy is awarded yearly by the USAF for the “most meritorious flight of the year” by an Air Force person, persons, or organization. The trophy is housed in the Smithsonian Institution’s National air and Space Museum. The award is administered by the U.S. National Aeronautics Association. The award was established on 27 January 1911 by Clarence Mackay, who was then head of the Postal Telegraph-Cable Company and the Commercial cable Company. Originally, aviators could compete for the trophy annually under rules made each year or the War Department could award the trophy for the most meritorious flight of the year. DeBellevue also received the Veterans of Foreign Wars’ Armed Forces Award and the Eugene M. Zuckert Achievement Award.

MiG Credits – Pilots, Aircraft & Weapons

The six MiG kills credited to DeBellevue in 1972 included 4 MiG 21s and two MiG 19s. All the MiG 21s were shot using AIM-7 missile and the MiG 19s using AIM-9L. Flights when MiG 21s were shot, the pilot was Capt Richard S. Ritchie. For remaining two the pilot was Capt John A. Madden, Jr. The aircraft flown for these six kills F-4D, AF Serial No. 66-0267, is now on display at the Homestead Air reserve Base, Florida; F-4D, AF Serial No. 66-7463, had six confirmed MiG kills, is now on display at the USAF Academy; F-4E, AF Serial No. 67-0362 was sold to Israel as a part of Operation Nickel Grass. Operation Nickel Grass was a strategic airlift conducted by the U.S. to deliver weapons and supplies to Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

Post-Vietnam War – Made a Pilot

The night of his fifth and sixth victories, DeBellevue was given transfer papers while being toasted at the military officer’s club. USAF had a policy of removing aces from combat. He was ordered by the USAF to enter pilot training at Williams AFB, Arizona, in November 1972, or accept his discharge from service. His stated desire to train Weapons System Officers. But the USAF felt that the highest ranking ace of the Vietnam War would not be a non-pilot. He was sent for pilot training, and after pinning on his new pilot wings, he returned to the F-4 as a pilot assigned to the 49th Tactical Fighter Wing at Holloman AFB, New Mexico. This was followed by assignments in Alaska, Japan, and many other airbases in USA. DeBellevue was the last American ace on active duty when he retired from active duty as a full colonel, while serving as commander of Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (AFROTC) Detachment 440 at the University of Missouri in January 1998 after 30 years of military service.

Honours and Decorations

On May 20, 2015, DeBellevue was one of 77 American flying Aces to receive the Congressional Gold Medal in a ceremony in Washington D.C. The Congressional Gold Medal is the highest honor Congress can bestow on behalf of the American people. He was a recipient of the Air Force Cross, Vietnam Gallantry Medal, Distinguished flying Cross among many others.

Air Force Cross Citation

Date of Action: September 9, 1972

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Title 10, Section 8742, United States Code, takes pleasure in presenting the Air Force Cross to Captain Charles B. DeBellevue (AFSN: 0-3210693), United States Air Force, for extraordinary heroism in military operations against an opposing armed force as an F-4D Weapon Systems Officer in the 555th Tactical Fighter Squadron, Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand, in action on 9 September 1972. On that date, while protecting a large strike force attacking a high priority target deep in hostile territory, Captain DeBellevue engaged and destroyed a hostile aircraft. Through superior judgment and use of aircraft capabilities, and in complete disregard for his own safety, Captain DeBellevue was successful in destroying his fifth hostile aircraft, a North Vietnamese MiG-19. Through his extraordinary heroism, superb airmanship, and aggressiveness in the face of the enemy, Captain DeBellevue reflected the highest credit upon himself and the United States Air Force.

Picture Source: Wikipedia

I had no idea whatsoever that WSO’s also qualified for ACE status. DeBellevue, achieved this status as a WSO is a huge credit to him.

LikeLike

Yes Sir, Earlier in the World Wars, there have been gunners and observers who shot or helped the pilot make contact and shoot have also been getting the “Ace” Status.

LikeLike